Olivia: My name is Olivia Melkonian and today I’m joined with our program manager Dr. Nik Matheou, a Cypriot activist within the Kurdish freedom movement and Sophia Armen, a Los Angeles based organiser, scholar and writer. Today we are going to be discussing the importance and relevance of organising across global communities, and also why the Armenian struggle does not end at recognition.

Sophia: My name is Sophia Armen, I am born and raised in Los Angeles, California where I am coming to you today. I have a hard time identifying in this way… but I am organising in the community here and I am a writer and I am also a scholar. My most recent work has been with two organisations, The Feminist Front, which is a grassroots youth organisation which is at the intersections of gender and racial justice; and the Armenian Action Network, which is a very exciting, new platform for research and advocacy for the needs of Armenians in the United States. Of course connecting our issues of social justice, to global justice as well.

O: Nik and I were talking about this as well when we were looking into the episode as well, but that article that you.. well I guess it was the conversation that was transcribed into the article in 2019.. about how activism for the Armenian Genocide is still an issue today. I remember reading it and it was kind of when I started using sounds and I got into telling Armenian stories through sound and it just really was the first literally like modern take on it and, I guess, an explanation as to why it is so important to today and why everyone has a role to play in it.

Nik: That was the way I found out about you as well Sophia and it was a real breath of fresh air to see the Armenian Genocide and activism for recognition being spoken about in this way because it has at least been rare in my experience to see people speak about it as an issue of racial justice that is immediately connected to other issues of social justice in the region, that has both it particular Armenian struggle and also it’s broader regional and human struggle. So really excited to talk today.

S: Appreciate it, and I just, because you brought it up, I want to say that the woman who I did the interview with was Banah Ghadbian who is a deep personal friend and sister organiser. And she really helped, I think, me be brave about trying to address many of the issues I think we are facing globally. And I say this only to affirm her incredible work that she has been doing. She is a Syrian Arab poet and really a daughter of the revolution. So I want to say that part of the easiest way to do these things is to do them in community and so that is why I am happy to be here with you all to continue those conversations in community.

O: So my first question for you is quite topical, you are based in the U.S., and the U.S. is on the verge, we hope, of recognising the Armenian Genocide. Nik and I are here in the UK; we don’t see any progression on recognition, so what do you think this means for the respective U.S. and U.K. based diasporas, and how do these governmental decisions impact our activism?

S: Right before this conversation (laughs) I was literally emailing different organisers across the U.S. to get them to urge Biden to recognise it, that I don’t think it is quite in the bag yet! (laughs) But I will believe when I see it, and I only say that because, especially the Democratic party unfortunately has often given us some false hope and promises. So I believe, a hundred percent that it is so possible, and that has to be the lifeblood of how we continue to work, but I just want to say that I don’t think it is guaranteed until it happens and then we will see it. (laughs) But I think we not only are in a prime moment for this recognition within the U.S. but it’s been a long time coming. And that is what I really want to emphasise, is that when the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate passed this in 2019, I received a lot of questions about you know, is this just the timing, why is this happening and I just have to emphasise even with Biden: the possibility of finally recognition happening in the U.S., right, that this is the product of one hundred years of struggle, of grassroots Armenian struggle, in this country, and also around the world. And this is not some coincidence. It is really because of the compounding effects of all of those generations who have fought. Those legacies all are needed so that each next generation can take it up.

S: And so unfortunately, and I say this unfortunately because it is just the truth for so many Armenians in the U.S., is that three generations of my family have fought for this within the U.S. and so many times we have heard the same response be--well it is not politically convenient, it doesn’t help America’s geopolitical, (sigh) imperialist interests in the region, we need to worry about Turkey’s alliance with the U.S., we need to worry about NATO, etc.--- and I think we really need to probe at why it has taken so long, more honestly, because I think other communities need to understand those dynamics that we face. And so, I want to say that if Biden, does recognise it, and he must, He must! It is a complete outrage, a moral outrage, that the U.S. has not recognised the Armenian Genocide because of these geopolitical interests. And if he does, it means that we have triumphed. Our grassroots organising, our activism has triumphed. That is what has won. I think what it means is, is that community organising, that our initiatives, that our building together does work.

S: So now when we talk about the U.K., and I am sure you all have much more insight on this than me, but what I will say is that so often the United States and the U.K. have essentially assisted with their global human rights violations or their lack of reckoning with history, right, or have been accomplices in repressive regimes around the world-- together. And often one will do something and one will follow suit and that is both ways. And so I am really hoping that if Biden does recognise the Armenian Genocide, which we are deeply hopeful will happen on April 24th this year, that that will encourage all global leaders to recognise the Armenian Genocide. And as we know this recognition piece in the Armenian struggle, in its history has always been only one slice of it, one part of it, and it is definitely not justice, but it is deeply necessary and needed.

N: I think that is a really important perspective to see these kinds of changes, especially when they go against the geopolitical grain, or they seem to go against the geopolitical grain, not as just decisions of governments like you say. It might be just a decision that they make because that option is available in a particular political moment, but what’s made that option available and what has given it the political weight that it has behind it is exactly the organising of generations of people on the ground. And I think, yeah, that can get lost very often in these kinds of struggles. I see it as well as the Armenian Genocide, also in Cyprus, with trying to get negotiations. We can't have a sort of lobbyist attitude to this. This has to be a continuous mobilisation.

S: We saw the House finally bring it to the floor in the United States, because we elected the most diverse, and the most women in Congress in the history of the United States. And it is no coincidence that finally the elements of the Democratic Party that were able to bring forward this global justice issue, happen to align in the moment with the community organising and with who was, then, in power. And so I also want to say that Biden’s election is thanks to the work of people on the ground, in especially Southern states, communities of colour, who really.. all of these pieces have to all fall in line for us to now finally be here in this beautiful, triumphant moment. So each of these wins are built on each other, just as the Senate was built on the House win. And so I always want us to think about that U.S. recognition is always connected to the other struggles that are happening in the United States and the more we empower those that are structurally disempowered in the U.S…it helps all people who are struggling.

O: So what do you think Armenian self determination looks like today and how do you think we can learn from these indigenous struggles that reimagine sovereignty? This question was kind of inspired by looking at the resistance of Armenians in Van in 1915 and looking at the same place today and the strong presence of the Kurdish resistance there which makes the city a historical and modern centre of survival against the same forces.

S: So I think, for one, when we talk about the Armenian Genocide as a system and structure of power, it’s not about a one time event, or a one time moment in history. So if we think about genocide as a structure of racism that replicates itself over and over again, then we are able to get at the root of what is causing it and how to prevent it, or how to stop violence. And of course, we know that the roots of the Armenian Genocide is a racial ideology, pan-Turkism, or Turanism, depending on how you want to frame it, but, in the experience of the Armenians this was very obvious in that the construction of “the Turk” was not only named as superior but anyone who did not fit that construction was a target of violence, and is to this day. And so that’s what we see: the refusal within Turkey to reckon with these historical ghosts… are still haunting everywhere. And it is very interesting I think that you all bring up Van, because I am Vanesti (laughs) and my grandfather’s father was in the self-defence of Van. His name was Anooshavan. And he is part of those absolutely fascinating Armenians who, unfortunately not only had to flee, but then left his family here and went back to fight in the self-defence of Van… all within the period of a couple years.

S: And I say this because I think people think of these moments in history very romantically, or abstractly, or outside of people who are living today, but the truth of the matter is just like my family from Van, my family from Kharpert, my family from Istanbul, my family from Hadjin.. we all still know where our houses were or are; we all still know the land that we are connected to. And the Kurdish struggle today in so many ways, though it is not the same and I want to emphasise that... it mirrors so many of the not only forces, but ways that people have had to resist those forces with the Armenian struggle, in Turkey. And we know this because it’s not just that, you know, Kurdish people are seen as second class citizens, but once again that the very foundation story of the Turkish state is unraveled by those of us who do not fit within this Turanist or pan-Turkist vision. And that there will be no peace without justice. Not only for these historical crimes, but for a justice that is forward-thinking, that thinks about a Turkey, or thinks about a region, in a much different way.

S: Because this racism, is actually also poisoning the people who are inflicting it. Because when you define yourself, based on the “othering” of communities, you will constantly have to perpetuate violence, in order to erase those other people, through every generation. And so, when we see Van today as such an important centre of the Kurdish struggle, to me I think that everywhere, and within every question, also are talking about Armenians. There is no future of justice, there’s no future of recognition, there’s no future of responsibility, even joint struggle without actually acknowledging these histories and understanding their connections.

S: And I would only add, because this question is so important, is when people think of the Armenian struggle as this past, you know, phenomenon, these people who were there, right - that is not a coincidence. That’s actually how indigenous people throughout the world are purposefully erased, right. Otherwise are not only having to acknowledge that they are there, but ask why they are not there. When we talk about 10-15 million Armenians, right (laughs) here I am talking to Armenians (laughs) across an ocean. We are talking about the living afterlife of genocide, in the flesh and blood: that is us. We are enough proof. There are more of us out here, and we live, we live these stories. Anooshavan had a child: my grandfather; my grandfather had a child: my mother; I’m here, her daughter. We are not some abstract historical text that is removed from the everyday reality of people who live on the land. And also for the Armenian diaspora from these events we have to learn about the current struggles that are happening on the land, from which we are from.

S: When we are talking about Middle East history, the erasure of Armenians and Assyrians is not a coincidence. It is part of that exact same Turanist logic, that mirrors our physical erasure.. and also the intellectual erasure of what we have contributed to this deeply diverse region! And I really believe it is of utmost importance, we have to fight erasure at all levels, at all times.

N: I think a couple of things that feel really important that you are pointing to is, one, about this discontinuity of a certain structure in the Turkish State, from the late Ottoman state into the Republic. For one thing, I think that’s the way we avoid some of the racism on our own sides. It’s something I see endlessly in Greek communities, in Greek Cypriot communities, against Turks, against this abstract, ethnic, sort of “barbaric” other that reproduces so many similar tropes to like nineteenth century racism around the Turk, and instead you have to locate this violence in a really specific historical thing. It is a State that has a beginning, has a middle, we hope that it will have an end and a different thing will replace it which will enable all of us to have a freer life. And I think that makes it much more concrete.

N: And it is interesting in the Kurdish freedom movement this is really clearly the perspective. It’s something that I notice straight away on slogans or demonstrations. It’s not Turks or Turkey, it’s the Turkish state. And it is interesting the conclusion that got drawn from this, like anyone who is sort of hearing something about Kurds, often they’ll hear this phrase “world’s largest stateless nation” and one of the friends actually said to me, in the movement, “they always say this like it’s a bad thing but I feel happy (laughs) I’m glad we never managed to get a state! I am glad that we never got this nation-state because it means that we don’t have this hang up on the state” When we are looking at self-determination like we were saying, it is about not having an exclusive claim but seeing a particular claim, and having an idea of self-determination that doesn’t cancel another one’s out. Where all of us claiming our history, where all of us reclaiming our role in the region, is a kind of value-added process. It adds more each time.

N: I think also, reflecting on the Armenian Genocide and the role of Kurds in the Armenian Genocide, Abdullah Öcalan issued an apology for that role in the nineties … it’s a big way they get to that. Like you said, if you look at this resistance today then the presence of Armenians is everywhere.

S: Those of us who have been, I think, part of the Armenian liberation struggle throughout history have always named the Turkish state as the source of oppression. But I also want to just name, because I often feel the pressure to have to say that repeatedly and I find that very interesting as someone whose entire family does not get to live on the land because in every way everyone was displaced that of course, one hundred percent, this is about the consolidation of that racism in the state and that’s the truth, right, that is what enacts this violence. But I also have to say especially as U.S. recognition might now finally be a reality after a hundred years is that there has to be, there has to be, a reckoning within the hearts of the public of Turkey and also Turkish society does not deal with these issues, which is that these are foundational, fundamental issues that affect everyone. That the people who are in Turkey, who are Armenian, are not a minority, they are who are left. And if you understand that within a historically legacy, you will also understand that not only should there be 20 million Armenians within Turkey today but we actually still exist out here and we can be in dialogue with you constantly, and we should be.

S: You have young organisers who are across the world, who are Armenian, who not only know their own history, but who are living proof and evidence of, not just the Armenian Genocide, but our continued stuck in limbo reality, right, in regards to these issues. We are also talking about our identity, and our identity across the world. And I think many Armenians, especially who are young today, think about “what is my place and relationship to this region, right? What is my relationship to Armenia? What is my relationship to Turkey?” And those are living questions, they are not a question of a hundred years ago. They are questions that are genuinely about our current day existence, and keep following generation after generation. You see, we have the same questions that emerge and pop up, and so instead of us continually asking for validation elsewhere, instead of us continually saying well our governments just need to get in line.. our struggles need to get in line! Our people need to be building this across differences, across communities. And if I were to say anything to the public of Turkey, honestly, to Turkish youth, who are incredibly struggling against their government on a day to day basis especially today, is that we are out here! We’re not myths. We are not dead people. Our families were not just people who were massacred and displaced. We are living, breathing people who have come from not only these communities but who have preserved these legacies, within our families, and who are building off them today. I really truly believe we have to be talking to each other, we have to building with each other and it is so not an issue of the past, it is such a current day, urgent, desperately needed, existential issue.

O: Why is Turkish identity mutually exclusive to the othering of these indigenous groups?

S: I think there needs to be an existential reckoning with Turkish identity and I believe that many communities fates are at stake. And if it's not the Armenians, and then the Kurds, or Greeks or you know, Jewish folks, etc. there will always be a new community… if you create identity and humanity based on this racial classification of superiority. And that’s really at the root of it. It’s racism. And racism is a system that I believe is the most powerful system in the world in so many ways, and it intersects with so many things but… its at the heart of so much of this violence and at the end of the day Turkish identity has to be challenged, itself.

S: But I really do not believe that Turkey will ever see true democracy, I don’t believe Turkey will ever have peace, honestly, for people in Turkey, unless we deal with afterlife of the Armenian Genocide. Unless we not only have an honest conversation, but right the historical wrongs through reparations, through completely, fundamentally changing Turkish society, right, for a more inclusive vision of what that means, to be from this land. And the mythologies are so powerful today it’s no coincidence that the “enemy Armenian” is still such a prominent figure in Turkish politics. If we get U.S. recognition, and U.K. recognition, our next question is now what? Right? Something that Monte Melkonian was talking about (laughs) decades ago. Now what? The Turkish public needs to have a mirror to itself. And that’s why this issue around the Armenian Genocide, its recognitions, its historical legacy, reparations, even the question of return.. what would it mean for Armenian diasporans around the world, the connection to the physical country, what is the status...I really want to bring this back up again because I don’t think it is just a closed question now that time has passed. When we are talking about that relationship, that is why it is so charged, because finally means sitting with those ghosts. And I think that is why Turkey is so afraid of opening it, because it will challenge people’s very identities that they have built on exclusion.

S: I want to meet people to have these conversations across borders because that is what is needed. And justice will not come from the U.S. government, it will not come from the U.K. government, all these things are deeply important on the route to what that justice looks like but ultimately it will happen in the people. And we are out here, not only to have those conversations, but to build those futures, that look like justice. And that’s my only hope.

N: It’s only by creating similarly robust structures that can anchor a different kind of ideology that it is ever going to be overcome. And it is only this that can make sense of the people who are raised believing in this mythology and then seeing so many identities that have to be denied.

N: So many massacres that just recognising their existence is an existential threat to them, and to everything that they’ve learned. And of course the Armenian Genocide, the Assyrian genocides, the expulsions of Greeks, the Pontic genocide, but also Alevis, the Dersim genocide, also the massacre of Marash. The existence or the potential for anything that could be even meaningfully called democracy in this land, in this space, depends on that question.

O: National governments regularly use “lack of evidence” as a reason to not officially acknowledge the Armenian Genocide. How do you believe oral histories can be used as evidence and how do they hold the power of autonomy for Armenians within our very hands and within our very homes?

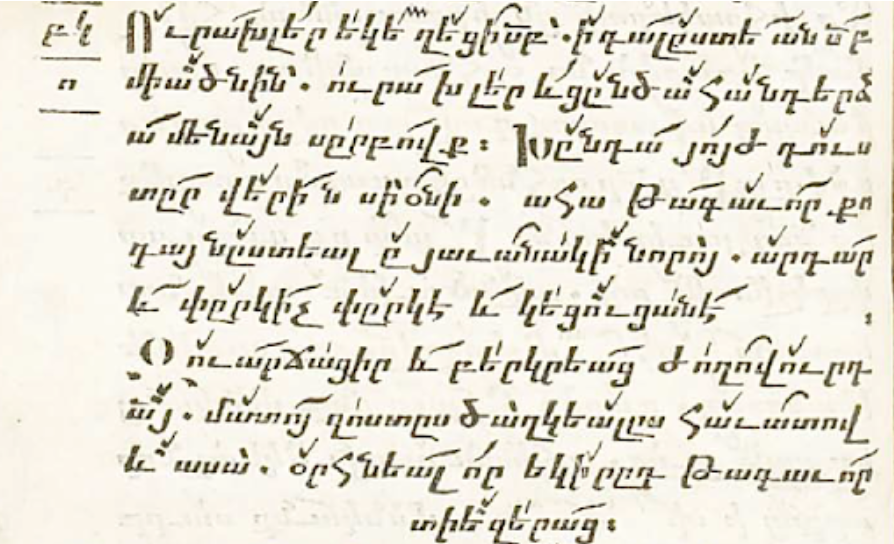

S: I think there is an over emphasis on number one, needing Western recognition as an idea, and number two Western academics as the arbiters of truth for the entire world so I don’t think that just because something that I would write about my family if someone else wrote it, makes it any better or worse, or less objective to be honest. And I think when we say even in the war recently, we see the kind of bias that we are accused of by birth and I think that is really unfortunate and does not get placed on Western academics in the same way, who are invested in power just like their governments and so we need to analyse that. And so if we understand that, that Armenians have historically been marginalised in Western archives... and we understand that Armenians have been largely erased… we understand that there are forces of power that have done that, but we also understand that there are parallel archives and that we have not let them go! (laughs) For example, the Armenian Institute are such a beautiful example of that right? Which is that Armenians have never just silently let our history go or let these stories die, right, we are actively organising, and building, and creating institutions and organisations to preserve them.

S: And so when we talk about how we can have evidence the truth of the matter is, is that one of the tactics of Turanism is to gaslight us and tell us that we are crazy, and that it is not true, and so that we constantly have to be proving it. And this is what the U.S. has done every year to the Armenian-American community, which is hmmm we’re not sure, massacres, you know “time of war” the same Turanist talking points. And so every year we have to essentially, what I would call, “bring out our dead” and it’s a deeply dehumanising process. It is reliving these stories over and over again. I know Armenians have at times felt like we need to fit these narratives to an audience, and that really isn’t true. We just need to speak them and not only preserve them, but, again, talking about their contemporary implications. And talk about them honestly and authentically, for what they are.

S: So the evidence of the Armenian Genocide doesn’t live in any master volume, it lives in the millions of us around the world. And we are proof enough in our very existence that we don’t live in our homeland. And that is enough. So our stories are the most powerful forces against that revisioning and that denial.