It has long been my custom, in congratulating friends who have achieved professional success, or are otherwise celebrating some happy occasion or other, to proffer, alongside my congratulations – շնորհաւորութիւններ (after all, շնորհ is grace) – my sincere խնդակցութիւն. Recently, upon congratulating a friend, I was asked to comment on the word խնդակցութիւն.

The root is խինդ – rarely encountered in this form, but giving rise to the noun խնդութիւն and to the very common verb, խնդամ. In modern usage, the word is a synonym to ծիծաղիմ, meaning “I laugh” – whence also the noun խնդուք, meaning “laughter”. Hence the expression քահ-քահ խնդալ, roughly corresponding to roaring with laughter, laughing out loud, laughing heartily (though not perhaps going as far as the internet acronym ROFL – “rolling on the floor laughing”!).

But in classical Armenian խնդամ means “I am glad”. The Three Archimandrites’ Lexicon of Venice (an unsurpassed publication, of which readers will hear more in the present series) gives gaudeo, laetor, exulto and delector as Latin equivalents, and ուրախ լինել, ուրախանալ, բերկրիլ, ցնծալ, հրճուիլ.

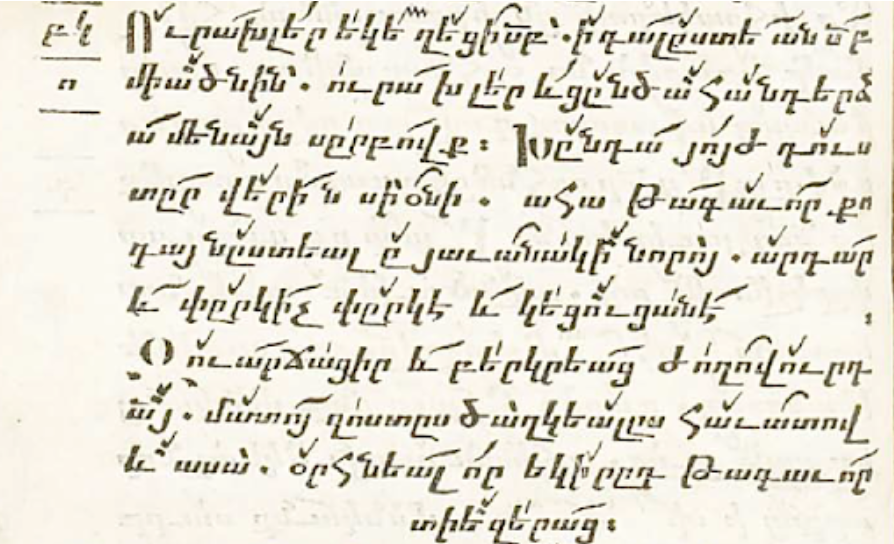

There is a beautiful Armenian hymn, which is sung on Palm Sunday, kneeling, and thrice, during the Vespers service immediately preceding the ceremony of the “opening of the doors”, Դռնբացէք. The second stanzas starts with the word, in the second person imperative – խնդա՛. In fact the stanzas just before – Ուրախ լեր եկեղեցի սուրբ, and just after, Զուարճացիր եւ բերկրեա ժողովուրդ Աստուծոյ – express very much the same sentiment as the one in question: Խնդա՛ յոյժ դուստր վերին Սիովնի – “Rejoice greatly”, or “Be exceedingly glad!” Courtesy of the National Library of Armenia, I have reproduced the hymn from the relevant page (p. 248) in the editio princeps of the Armenian Hymnal (Amsterdam, 1664-1665), herewith. I have also attached a recording of this stanza as sung by one of the most musicianly interpreters of Armenian hymns I have encountered, namely Zareh Srpazan of blessed memory, Archbishop Zareh Aznaworean (1947-2004), whom I was extremely lucky to count amongst my own teachers.

To add a bit of visual interest, I have included this image, which appears in a seventeenth-century հմայիլ or hmayil (prayer-scroll amulet), kept at the Matenadaran Institute in Yerevan. It appears just above a prayer from the Book of Lamentation by St. Gregory of Narek: the Saint himself is evidently portrayed on his knees, apparently officiating during a service of Դռնբացէք, which in the olden days used to be held literally outside the church, until the doors were ceremoniously opened, after hymns were sung, psalms recited and prayers said. I have also included a photograph of Zareh Srpazan from a Palm Sunday service (albeit not from the Դռնբացէք, but from the Պատարագ, the Divine Liturgy, celebrated earlier in the day), probably from around 1981.

Now կից has several senses: it usually means “adjacent”, but is often used to convey the sense of “alongside”, “together”, “similar”, and “equal”, and thus corresponds to the prefix “co-”. A co-adjutor Catholicos is thus an աթոռակից կաթողիկոս – one whose throne is adjacent to that of the catholicos “proper”, as it were, but also with similar powers and status. The word գործակցութիւն means, by the same token, “co-operation”. (I do urge my students to avoid the ungainly but distressingly widespread համագործակցութիւն – a grotesque tautology, roughly corresponding to“co-co-operation”!)

As it turns out, խնդակից is attested in an old translation of the great Jewish philosopher, Փիլոն Աղեքսանդրացի (Philo of Alexandria – many of whose works have been preserved in Armenian alone, the original Greek texts having perished); at one point he writes:

Լսօղքն խնդասցեն, եւ խնդակից լիցին, which we might translate as “Those who hear shall be glad, and share in the joy”!

Accordingly, in offering friends my խնդակցութիւն, I am letting them know that I share in their joy, and that I too am glad, as they are (by the same token, alas, whereby one may offer condolences using the word ցաւակցութիւն – sharing their pain, c‘aw).

Allow me to commend this underused word – for its numerous and entirely joyous associations, its ancient and well-attested roots, and, not least, for the empathetic and positive sentiment that it embodies. Surely it must bespeak of true friendship. After all, as another late teacher of mine, the conductor Carlo Maria Giulini used to say, any reasonably kind person feels sympathetic towards someone who experiences suffering; but being able genuinely to share in the gladness experienced by others is one of the marks of genuine friendship.

Written by Haig Utidjian