Some of the most influential figures of Armenian feminism hailed from the multicultural Ottoman capital Constantinople. The city, which we endearingly refer to as Bolis, was home to an innovative Armenian community which spearheaded almost all cultural, architectural, and socio-political movements within the empire of the period: feminism was no exception.

Mari Beyleryan

Propelled by an amazing constellation of intellectuals such as Elbis Gesaratsyan, Nazli Vahanyan, Srpouhi Dussap, Mari Beyleryan and Vartuhi Nalbandyan, Western Armenian feminism not only highlighted the multifarious trials and tribulations of Hay women, but also evoked the possibility of empowerment through a series of publications beginning with Guitar and The Eternal Bride as early as 1862. In one of her seminal essays later gathered under Namagani ar Intertsaser Hayuhis (Letters to Educated Armenian Women, 1879), the first woman journalist and the editor of Guitar, Elbis Gesaratsyan’s, would encapsulate the feminist response to the zeitgeist in the following manner:

‘You may have often experienced women who [are] more thoughtful, more foresighted, and more hardworking than their husbands, but they knowingly and blindly succumb to men who do not know the right way to do something. Because the woman should be a bird without a tongue and the man, even if a crow, must sing and rule with pride. Yes, my sister, these are my thoughts. Our opinions should blossom. Capable persons must take this up as a duty: [they] should activate sluggish brains in lawful ways, be vigilant about holding onto their freedoms and encourage other women to educate themselves. We should create reading rooms, societies and acquire the knowledge required to reach both the hearts and minds, so that we can take steps on the way of development and be counted as human beings.’

Elbis Geseratsyan

Hayganush Mark

A year later, when the girl who was to recalibrate the thematic and pragmatic boundaries of feminism to the specific needs of the Armenians was born, the path had been paved by these exceptional feminists who set the blueprint for the women of both colonizer and colonized groups of the empire. At this time of relative peace and liberal progressiveness, the young Hayganush Mark was encouraged to send her poems to newspapers and journals such as the bilingual Manzume-i Efkar, Panaser, Purag and Puzantion while still a student at Yeseyan High School. In fact, she is said to have been assured of her future occupation after becoming a semi-finalist in a poetry competition organized by the Armenian weekly, Masis when she was only 17.

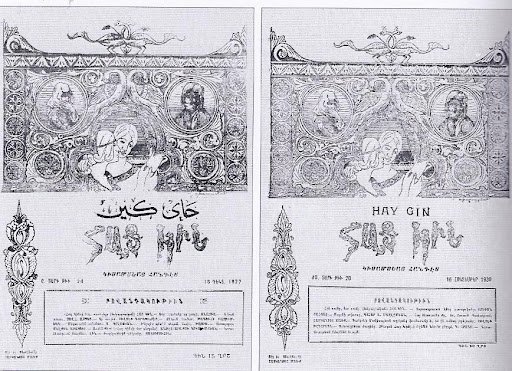

As we reflect on the remarkable achievements of these pioneering women every year in March, may we become active participants in their undying devotion to women’s empowerment, which is so beautifully embedded in the inherently resilient and innovative Armenian spirit of Hay Gin, the only feminist magazine to begin its life in 1919 as an indigenous component of a multi-cultural empire and complete it as a minority in a nation-state in 1932.

Srpouhi Dussap

Hayganush Mark portrayed as the bearer of Armenian Women Association on her left hand and Hay Gin on her right (1921).

Text by Dr. Tamara Wilson

Wilson is an award-winning poet, academic and research fellow at the University of Roehampton, London. Alongside the investigation of postcolonial legacies in literature, she is interested in the exploration of identity and memory in categorisation-resistant hybrid literary forms from a feminist perspective.